“Algorithms are able to be creative… And so in their very nature, they are showing and exploring new ideas.” Ai-Da’s creator Aidan Meller in an article about “her” design exhibition at this year’s London Design Biennale

Creative professionals around the world are faced with the introduction of user-friendly generative AI tools offering a plethora of services for anyone with half a mind to design the right prompts. Prompt design is itself emerging as a potential new job title, while the old human ones such as writer, artist, graphic designer, or even, visionary are coming under pressure to figure out where they will stand in this emerging future. With a soupçon of nous and a bit of luck, the future prompt designer can churn out umpteen illustrations visualizing an imagined Utopia for humanity – the one where we grow 6 fingers and smile like one of Käärija’s backup dancers.

It got me thinking about competitive and comparative advantage (of humans) – an old skool concept from B-School textbooks. Michael Porter’s generic strategies are too limited for business models built on human creativity. The independent creative practitioner, the design freelancer, or the artist working off commissions gleaned through their social media networks are micro-enterprises and creative industry SMEs are the mainstay of their sectors. In the Nordics, almost 60% of micro-enterprises are sole traders and firms with 5 or less people comprise around 90% of all enterprises registered in Finland.

The challenge of technological advances eradicating or undermining skilled occupations or entire lines of revenue is not a new one. Its been around since humanity’s tool-making capacities generated skilled tool-makers and inventors – the artisans and craftsmen who advance the field for skilled practitioners and amateurs alike. In this categorization, I include the development of desktop publishing (DTP) as tools for creative expression.

However, I am not sure if generative AI apps are necessarily “design tools” in quite the same way as DTP, except serving to enhance DTP services. Once the game of playing around with prompts becomes boring, creators begin to recognize that the fun parts of creative work have been stolen rather than the tedious bits which, until now, our tools were designed to address. Labour saving technologies are not quite the same as cost saving replacements.

When you punch up something, you’re usually brought in for a small rate to do everything from adding jokes to helping fix the story. Very, very often this work is not credited. You’re basically coming in as a freelancer to help out. It’s fun. It’s a good side job. But, for the vast majority of people, it’s not a reliable job that can pay all the bills. (source)

How this will play out in the near term

Cheap, free, or one low monthly subscription to generative tools based on AI has, can, and will commodify entire creative subsectors – particularly for journeymen and masters. The maestros will always survive such an upheaval, in the same way that we still recognize the space and role for a hand-stitched suit or a handmade shoe in the era of mass production. The pressure will be on price and no human being can match the price-performance ratio of an AI tool in head on competition.

Rather than having humans at the creation of the work – and getting full credit for it – there’s a chance that creative industries will try to use AI as a loophole. They’ll generate an awful sci-fi script nobody wants to make, hire a skilled person to rewrite it entirely, and then use legal dodging to withhold (or drastically water down) credit. Not to mention the pay rate. It’s not your work, even if you did a massive amount of work on it. (source)

The horse did have to give way to the steam engine. And, the horse population declined until they evolved into pampered pets or super-athletes competing on the race track. Writers are already on strike and as the linked article in the quotes above show, the author is not concerned about the indie maker or creator using technological help where budgets won’t stretch to cover the costs of an production team. Its the big corporations with the expensive versions of these generative technologies who are demonstrating their power to transform the market interface for creative work.

Within design publications and community boards like Core77, the discourse trends towards adjusting, adapting and adopting the technology. That is, we are treating the advent of generative AI in the creative sectors as a tsunami or a volcano eruption – a force of “nature” that we, as humans, cannot control or do anything about. We, the humans, must change in response to this technology – it did not magically appear out of thin air, mind you, nor was it the result of tectonic forces of geology. There is a difference in degree and level of change to existing creative practices and processes that AI brings forward unlike a Photoshop app simply due to its algorithm’s creative nature as Ai-Da’s creator said above.

Meaning-making, magic, and motivation

Our creative expression is as old as our biped ancestors who painted on the walls of their caves in the light of the flickering fire, telling stories of brave deeds and great hunts, leaving their handprints to show their opposable thumbs. The millenia old legacy of humanity’s creative spark was not dominated by Science and the Western Knowledge System until the Enlightenment intermingled with mercantilism, exploration, and subsequently colonization and capture. AI – the large learning models and all their accoutrements in the form of datasets scraped from vast troves of human-generated knowledge – is completely path dependent on the scientific method and the Western knowledge system. Human creativity never was, and does not need to be.

“I started exploring Midjourney, where the quality was next level but it was deficient in Māori design, which I believe is a good thing. So I saw myself partnering with AI to produce base images where I would add my own detailing.” Te Ari Prendergast, (source)

Few have yet to step back and consider AI-generated creativity against the backdrop of our knowledge systems and the landscape of our advanced socio-technological society. When we do so, we see systems level opportunities that go beyond any one single creative practitioner’s opportunity to contribute from their peoples’ Indigenous knowledge.

Sir Apirana Ngata in his famous quote “E Tipu e Rea” encouraged his people to thrive and grow using the tools of the modern world “but let your heart be guided by your ancestors”. In the context of artificial intelligence, this quote could mean that, while we should embrace and utilise tools such as AI, we should also honour and draw upon the wisdom and values of our ancestors to ensure that we use these tools in a way that benefits both the health and wellbeing of our communities and the environment ~ Te Ari Prendergast, (source)

The author of the quote above is in a discussion at the source about Ethics – seen as the role of humans in the AI generated sphere. The conversation does not explore the important insight on Ancestor mind any further, but instead, veers back to Plato and Homer – pillars of the western knowledge system. It is here that one opportunity space emerges for human creative practitioners to upgrade their own ways in thinking, in the face of technological artefacts that mimic their thinking. If our hearts are to be guided by our ancestors who left their marks in red ochre all over our shared planetary home, then what we can do is begin exploring older knowledge systems and alternative ones. AI cannot do that, its algorithms are designed on principles, protocols and programming that emerged from and are firmly situated within western science.

“An ecology of knowledges”

Humanity has available to it more than just one knowledge system, for ex. Indigenous, local, traditional ways of knowing; embodied and experiential ways of knowing (practical hands skills, kinaesthetic learning and spatial intelligence; muscle memory and intuitive perception, et cetera). Generative AI tools are advances in technology, science, computing et al., in the service of artificial knowledge processing and creation. Humans can use the same approach to future proof themselves – by diving into alternate ways of human knowing, doing, and making thereby expanding their own ways of thinking beyond the currently dominant “scientific mode” or “western knowledge system” and its well documented limitations.

… the future we’re facing isn’t one in which people are outright replaced. Rather, they’re reduced. They’re demoted. While you’re paying more and more to enjoy those products, the people who actually make them are getting paid less and less. It’s bad enough now. We’re trying to do something before it’s even worse later. (source)

We, the people, can expand our recognition of a plurality of ways of knowing as the first step to thinking around the rectilinear propagation principles underlying western scientific thought and sparking the multi-coloured rainbow of creativity in the prism of our mind’s eye. I can allude but not all the generative predictability of the next word could have communicated metaphorically yet concisely and clearly the content in the previous sentence, no matter how powerful and advanced the artificial thing is – it has no capacity for meaning making or magic, nor is it motivated by intent or agency. Creative output, regardless of technical quality, will never be infused by the pain we know existed behind each of the brushstrokes in Van Gogh’s Starry Night. We need motivation in the face of imminent systemic transformation of the buyer’s market for creative work. We need motivation in the face of replacement, redundancy, or reduction. Channeling our Ancestor Minds is one way we can “kick it up a notch” as some cook once said.

Cognitive justice encompasses not only the right of different practices to co-exist (which is a necessary condition nevertheless), but entails an active engagement across their knowledge-systems (Visvanathan, 2005, 2009). In practice, cognitive justice is given shape through an ‘ecology of knowledges’: an active dialogue between different forms of knowledges and practices, both scientific and nonscientific (Santos, 2014). It involves rethinking the way in which knowledge emerges in modern science, where one side produces and the other passively consumes. It challenges the ‘monocultures of the mind’ (Shiva, 1993) and calls out the external limits of modern science, i.e. dimensions rendered invisible by reductionist epistemologies (Santos, 2007, 2014). Coolsaet, 2016

Generative AI cannot follow us outside the external limits of modern science – not only due to its dependence on the content it has sucked up into its probability based predictabots, but also due to the boundaries that describe and define its creators’ ways of thinking and knowing; firmly grounded in and credentialed by the best that western science and knowledge system has to offer.

There’s “thinking outside the box” and then there’s cognitive justice.

The beautiful part of the nature of human creativity is that each creative practitioner has their own skills and talents. If there’s any group of people who are already well prepared to embrace and enhance their different ways of understanding the world around them, of generating knowledge and meaning, and of communicating and sharing it, it is the artist and the writer and painter or the maker. Industrial designers, for example, already weave together different ways of knowing when they build a physical prototype to test their ideas – the very act of building is knowledge creation in action. We can have an ‘ecology of knowledges’ to use Coolsaet’s phrase and then we’re not sitting ducks in a single knowledge system watching the technological tsunami wash our shoreline away. In order to achieve this, we must embrace the principles of cognitive justice and expand our awareness – as human creatives – outside the box defined and described by western science and the protocols of its knowledge creation and dissemination mechanism.

This space is where my head has been at for most of this year, beginning at the end of 2023 when I was appointed advisor to a master’s thesis project that asked the motivating question “What is the role of design to facilitate integration of local, traditional, and indigenous knowledge into disaster response and preparedness for at-risk communities?” In parallel, our team had another master’s thesis project that explored the loss of vitality thinking in western society and ways to revive this experiential knowledge through artistic practice. As of this past week both projects have been completed and the insights from our analysis offer us strategies for revitalizing creative practice for arts and design through the exploration of all our human senses and alternate ways of knowing, being, doing, and most importantly, making.

Once I include the insights from horizon scanning, it becomes clear that future proofing ourselves at this moment in time not only implies a re-orientation towards planet-centered work on climate related issues and the environment but also an expansion of our own human knowledge generation practices and processes in order to create holistic solutions for this systems level problem space.

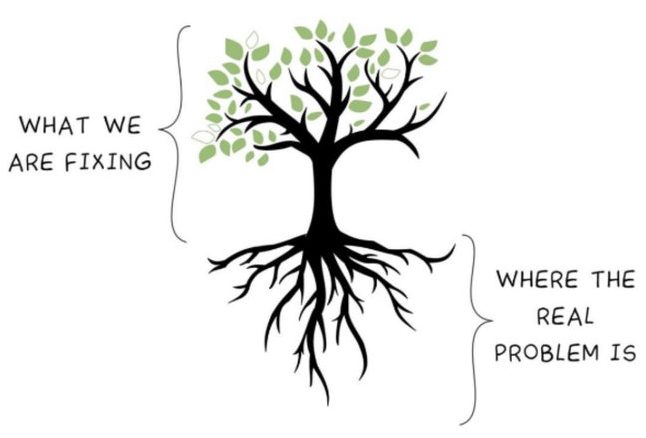

This illustration on worldview and systems design is only one example of the ways that embracing and exploring alternate ways of knowing, of knowledge creation and dissemination, of learning and seeing, that can enhance our human capacities. Our responses to generative AI is not the binary decision (adapt or die) it is being perceived to be – even the tendency to view the world in a binary terms is a limitation of the Cartesian mind/body divide and whatever else the church, state, and scribe nexus was upto back when they were relegating all life as brute mute nature to be exploited for their own gain. See Nutmeg’s Curse for details.

We are preparing ourselves – as creative practitioners – to disrupt the current paradigm simply by thinking out of the box of the dominant knowledge system and its science and technology. We can share our thinking tools with you.