There is yet one leverage point that is even higher than changing a paradigm. That is to keep oneself unattached in the arena of paradigms, to stay flexible, to realize that no paradigm is “true,” that every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe that is far beyond human comprehension. It is to “get” at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. ~ Donella Meadows 1999:19

Last week, I finished revising a manuscript where I had been asked by reviewers to expand on the implications of changing my research paradigm for social design praxis. Two days ago, I woke up with the realization that if changing my  paradigm could effect a certain change in the social intervention I would design and then implement, would that not imply that using different research paradigms to effect different design outcomes were, in effect, design tools? In fact, it would be fun to ask a number of teams working on the same design challenge to each choose a different research paradigm as the basis for developing their project goals. The comparative analysis of the outcomes would be utterly fascinating.

paradigm could effect a certain change in the social intervention I would design and then implement, would that not imply that using different research paradigms to effect different design outcomes were, in effect, design tools? In fact, it would be fun to ask a number of teams working on the same design challenge to each choose a different research paradigm as the basis for developing their project goals. The comparative analysis of the outcomes would be utterly fascinating.

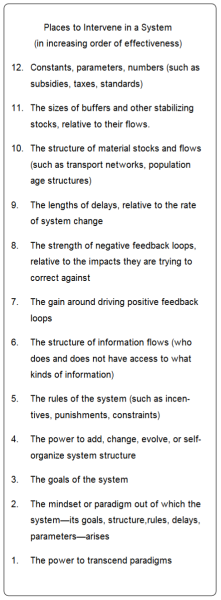

That is, I need not remain simply at the level of changing my paradigm as the outcome of embracing entire knowledge systems* as design materials, I could take a step back – as I have always done on this blog – and look beyond the obvious. I could consider all the epistemological constructs – such as paradigms – that make up knowledge systems as tools for social design. This morning, it was pointed out to me, through a link to Donella Meadows (source of screencap on the right), that my pondering had a basis and its roots were in systems thinking, one of the pillars of my own work – whether I have recognized it or not. Or rather, whether I only began to recognize it after returning to university to add a layer of academic inputs to my intuitive knowingness.

…everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment. If no paradigm is right, you can choose whatever one will help to achieve your purpose. Donella Meadows 1999:19

* The preliminary logic for this is currently under wraps for another 6 weeks, but be assured that this blogpost will be updated as soon as possible.

Transposing acquired knowledge and domain expertise from the informal economic systems to socio-ecological systems

This longish extract from Hummels 2021 offers a clear hint where I can contribute from my own decades of observing informal economic systems.

…economic developments emerge (or have emerged) in conjunction with scientific and engineering developments, opening up new ways to understand and engage with the world. Priogogine and Stengers show that the history of western thinking is deeply interwoven with three scientific paradigms: 1) the classical-Christian view developed by, e.g., Aristotle, Ptolemy and Thomas Aquinas; 2) the classical- scientific view developed by, e.g., Newton; and 3) quantum physics, relativity, and the dissipative and self-organizing structure view developed by, e.g., Einstein, Bohr and Prigogine. Einstein’s theory of relativity shattered Newton’s classical-scientific view based on objectivity and predictability. And Prigogine’s world is complex, open and non-reversible, which is opposite to Newton’s closed system, modelled according time-reversible physical laws.

Looking at this historical overview of economies, the vast majority seems based on a classical-scientific view. To address major challenges like poverty and climate change, the World Economic Forum urges building our economies upon a paradigm acting upon principles of complexity. Developing open, complex systems, admissible to change and based on interconnections that cannot be reduced or brought back to separate element disrupts the dominant adage of certainty, truth, simplicity and objective knowledge. Vermeer states that by developing resilient complex systems, we might be able to handle external shocks or disruptions like global warming or Covid-19. (Hummels 2021:99-100)

There are embedded implicit assumptions in this extract that are worth pulling out and examining. First, social economic systems such as cross-border trade in East Africa, exist and do not need to be designed. They are “open, complex systems, admissible to change and based on interconnections that cannot be reduced or bought back to separate elements” (see the efforts to replace brokers in the farm to fork value chain with digital platforms for example). To debate whether the informal trade in food commodities and fresh produce in the East African community is a socio-economic system or socio-ecological system or even a socio-technological-ecological system now that mobile phones have made a permanent home within the system is something I’ll take up in later blogpost, it would make this one far too long. The point is that, from the perspective of the formal knowledge system and its paradigms, this system does not exist yet it provides “livelihoods, lifestyles, and life chances” (Visvanathan 1997) for the Majority World. Its existence thus resists the assumption embedded in the two paragraphs above that such as system needs to be deliberately designed. Why re-invent the wheel that has sustained itself for centuries and is endemic to communities and peoples around the world? Far better to consider it a working prototype of what designers aspire to achieve with their design skills in the arena of transforming economic systems. The next paragraph written by Hummels I share below:

The historical overview of economic and paradigmatic shifts also shows a continuation of previous paradigms after the emergence of new ones, although older paradigms are losing influence gradually. The difficulties of finding our way out of major societal challenges, are signs that shifting to a new paradigm is difficult. The simultaneous existence of different societal paradigms can lead to fierce tensions and conflicts, since paradigms by definition do not align and are based on different sets of values and beliefs. Given these tensions, we argue that it is not enough to develop alternative abstract economic structures, organizations and models that might address societal challenges. We pose that a transformation of concrete economic practices is needed to bring new emerging paradigms to fruition, while recognizing the historical development of older paradigms. (Hummels 2021:100)

Operating from within the confines of the Euro-Western academy and the epistemological paradigms of the Western Knowledge System, Hummels articulates the tensions between a ‘new’ and ‘old’ paradigm, whereas my own observations, literature reviews, and structured qualitative research over a period of years demonstrates that the tensions she describes already exist, have long existed, and will continue to exist between the formal and informal economy where ever the informal economic system dominates the revenue generating capacity of the majority of the working age population. Thus, it is not a ‘new’ paradigm per se so much as it is an old one, a legacy of colonization (see Bankoff 2001 on the deliberate creation of paradigms that render vast swathes of the world incapacitated by their own environment and thus in need of intervention and help i.e. the premise of international development). These are all long established research strands and discourses in development, decoloniality, and indigenous scholarship. However, they are all ‘new’ to the discourse of design which is only now thinking about the conflicts and contests between the hegemonic ownership of knowledge production, its power to represent the Other and their ways of knowing, being, and doing. For design, alternative economic structures need developing and designing from scratch, informed as it is by only the paradigms and social structures of the Euro-Western academy. Looking at it from the interface between non-Western and Western knowledge systems and their clash of conflicting worldviews, epistemes, beliefs, and thus paradigms, makes clear that what Hummels has described as a direction for transforming economic systems is actually a direction that humanity has long embraced and practiced for generations prior to the design and imposition of the European colonialist market economy and its deliberate attempt to exclude the natives and/or raise barriers to their inclusive participation and recognition within a wealth creation system designed only to extract and exploit “resources” (see Nutmeg’s Curse for how both humans and the rest of nature were rendered inert, mute, and brute assets or resources to be sold and exploited for profit).

Paradigm change or changing paradigms?

Thus it is not a new paradigm that Hummels’ system change requires so much as for us to see how our perspective changes when we change the paradigm by which we see the world. What becomes visible? What has always existed but has long been marginalized, suppressed, or erased from view? When I put down the paradigms of the Western civilization and pick up indigenous ones, such as Chilisa’s (2019, 2012) I see a whole different world come into light. I see that what Hummels describes is actually a reflection of the limits of one singular knowledge system as it hits the challenges of its own assumptions and worldviews in a world that has resulted from its hegemony. Not only are we now radically empowered by Meadows’ observation that we have a choice of paradigms by which to view our human systems but we can see that we have more than one knowledge system available to us. Shifting the focal point of our perspective can double our knowledge base overnight. With that paradigm change alone we can transform our systems. In the power struggle between knowledge systems (Chilisa 2019; Smith 1999), changing paradigms is but a reflection of Meadows’ sense of radical empowerment. No single knowledge system has the capacity to navigate the complexity and plurality of challenges we face, particularly on the epistemological level. The sustainability sciences have long begun to embrace the notion of working with two or more knowledge systems, although they stumble on the same limits we can see clearly in Hummels’ arguments above. Design has yet to embrace this versatility in its knowledge base.