It is purely by accident that I stumbled on Justin Yifu Lin‘s 1995 article “The Needham Puzzle: Why the Industrial Revolution Did Not Originate in China” this morning and my thinking on the nature and function of the processes of innovation has been significantly elevated. A short quote encapsulates Lin’s hypothesis (1995:275-276) sets the context for my discussion.

However, what really distinguished the Industrial Revolution from other epochs of innovation bursts in human history, such as the one in the eighth- to twelfth-century China, was its sustained high and accelerating rates of technological innovation. The problem of China’s failure to initiate an industrial revolution in the fourteenth century, therefore, is not simply a question of why China did not take a further step to improve its water-powered hemp-spinning machine. Rather, the question is why the speed of technological innovation did not accelerate after the fourteenth century, despite China’s high rate of technological innovation in the pre-fourteenth-century period.

The key to this question may lie in the different ways in which new technology is discovered or invented. The hypothesis I propose as a likely explanation to the Needham puzzle is as follows: in premodern times, technological invention basically stems from experience, whereas in modern times, it mainly results from experiment cum science. China had an early lead in technology because in the experience-based technological invention process the size of population is an important determinant of the rate of invention. China fell behind the West in modern times because China did not make the shift from the experience-based process of invention to the experiment cum science-based innovation [process], while Europe did so through the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century.

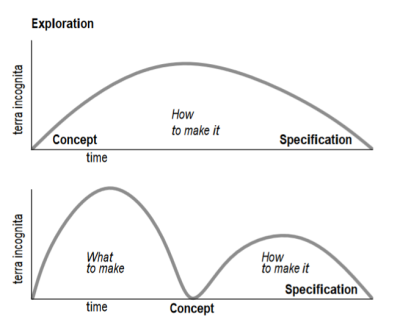

While the remainder of Lin’s article situates these approaches to innovation within an economics-based discussion, and is certainly an insightful read, in this blogpost I will step back from these details to consider his distinction between experience-based and experiment-led innovation processes from the perspective of design. Figure 1 below visualizes the late Charles (Chuck) Owen’s creation of deliberate space for exploration and discovery of a complex problem space at the front-end of the design process. This is visualized by Owen as the difference between the two line diagrams, where the clarity arrived at for planning subsequent design actions and mobilizing is denoted by the concept. That is, what Owen does is separate the period of uncertainty from the period of clarity for the knowledge work undertaken during design.

In Justin Yifu Lin’s terms, we can correlate the unstructured and quite random approach of trial and error that characterizes the experience-based technological invention process (Lin 1995:277-278) to Owen’s 1-step process of designing, and the use of the scientific method for knowledge creation and a structured methodological approach to experimentation for knowledge generation and iteration to Owen’s 2-step process. That is, the front-end work is where knowledge is created in advance of teh technological innovation and provides epistemic infrastructure to increase epistemological productivity. This contributes to accelerating teh rate and pace of technological innovation within the sandbox for which scientific research produced knowledge. However, there is one gap that Lin’s argument fails to consider and it is that which is filled by design knowledge (without which you cannot really make improvements to machine design, in this case the water-powered hemp spinning machine). This is not a reflection on the respected economist so much as it is a chasm between an economics degree and engineering and design education.

The component of knowledge that is missing in Lin’s distinction of the two approaches to innovation is practical and experiential knowledge gained from the building of a working prototype in the first place and then testing it in the real world. This is captured in Owen’s diagram by the words “How to make it”, a motivating question fundamental to design and engineering disciplines and often irrelevant to a vast majority of other studies, such as for example, economics or history. That is, science accelerated design and engineering but design and engineering existed around the world prior to the Industrial Revolution. Experience-based technological invention process may indeed be based on trial and error as Lin says but what the experiment cum science based innovation process does is create infrastructure such as waymarkers, guidelines, roadmaps, milestones (et al) for giving structure and direction to the resources invested in technological invention. Knowledge shows the direction to take in our experiments with a hemp-spinning machine’s design thus our trials and errors are not completely blind but informed by theory and by exploration and discovery in order to narrow our focus on to one or two conceptual directions to develop into prototypes. The prototypes help us figure out whether our concept can even be made and thus answers the question of how to make it. What Owen did was create space for us to figure out what to make before leaping straight into the trial and error development of a concept. This then is what he described as design planning, and the outcome of a concept is a planning document. In turn, design planning accelerates the process of innovation by scoping the boundaries of the space within which experience-based technological invention occurs. That is, in Owen’s development of the 2-step process of planning and design, he combines the best of both approaches distinguished by Link (1995).

At this point, it is difficult to ignore the conjecture that if China invested heavily in human-centered design education around the turn of this century and also in design planning (particularly in Tsinghua and Hong Kong Polytechnic iirc) then China’s accelerated product development and technological inventions and innovations reflect not only their historical strengths in experience-based technological invention process (see Shenzhen’s rapid and numerous variations as real world product design research) but are now combined with experiments cum science-based innovation that Lin articulates as the accelerator for the Industrial Revolution that overtook China’s multi-century lead. That is, China has the equivalent of booster fuel in their legacy engine for technological prowess.