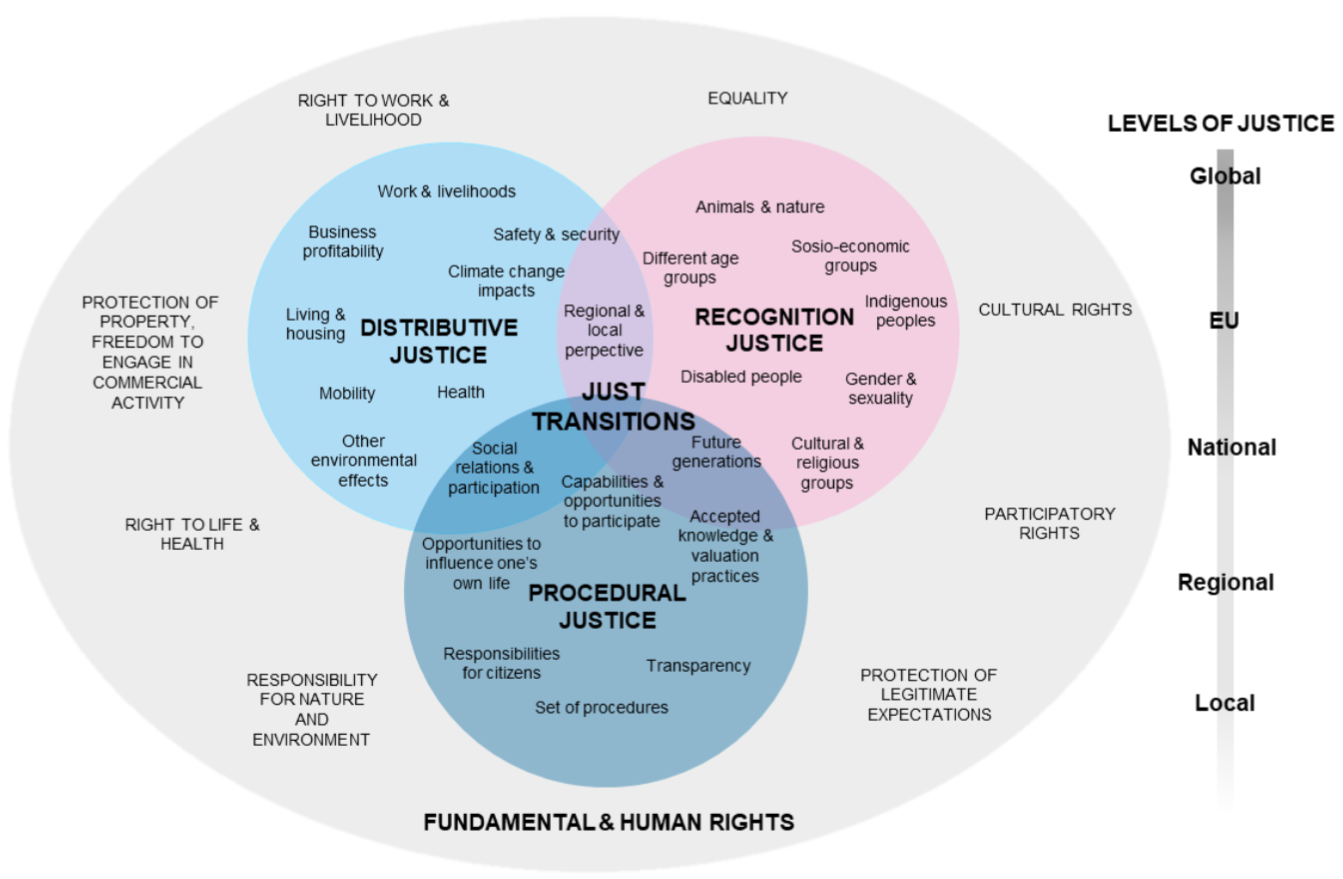

What is interesting in this diagram from Kivimaa et al. (2021:7) from the Finnish Climate Change panel, is the missing component of Indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge from the sphere of Recognition Justice. Why it is interesting is because the authors cite Tribaldos & Kortetmäki (2022) among their references for the concept of justice, who in turn give space to the need for ‘respectful pluralism‘ (pg. 252) which includes knowledge systems and knowledge holders not otherwise be recognized by the academy. Culture alone is not enough to encompass the diversity and heterogeneity of knowledge traditions (Nakata 2007:197-201), even within allegedly exceptionally homogeneous Finland (submitted for review), and overlooking a plurality of knowledges, and their deep interconnection to livelihoods, lifestyles and life chances of a people is the very meaning of Cognitive Injustice (see Visvanathan 1997, 2005, 2009). Cognitive Justice advocates for the recognition of a plurality of knowledges, and for respectful engagement with the diversity of knowledge holders on their own terms without having to submit to the hegemony of the Euro-western knowledge system and its social structures (Coolsaet 2016; Martin et al. 2016; Rodriguez 2017; Visvanathan 2005).

Cognitive Justice as an essential component of Recognition is thus deeply interconnected with elements of both Procedural and Distributive Justice, even as its implementation mitigates expert bias and group think – factors not only recognized as issues in Finland’s governance mode (OECD 2022) but also as an inadvertent driver of social injustice throughout the country (Salmi et al. 2022; Mustonen 2009, 2013); Kuokkanen 2007, 2011). To be fair to the authors, it is difficult for a fish to recognize water – as we saw yesterday when diving in Donella Meadows’ articulation of deep leverage points in a system. Linking the role of knowledge to all the other factors in the diagram is beyond the scope of this blogpost – its a research project in its own right. However, enough hints can be gathered simply by pondering the issues most closely related to Just Transitions at the center of the Venn Diagram and asking how our different knowledge traditions and systems influence our experiences, our worldviews, our beliefs, and of course, our epistemes (Kuokkanen 2007). Problematizing the power struggle between ‘researcher’ and ‘researched’ is the first principle of emancipatory research paradigms (Chilisa 2019; Smith 1999). This factor, however, is alluded to by Kivimaa et al. (2021) in their report where they remind the privileged policy planners (and I add, scholars) to remain cognizant of their power (pg. 18).