Justice has become the hottest topic in calls for papers this year, particularly noteworthy in inter- and cross-disciplinary design and innovation studies. I first came across the theme of justice last year in the IPCC February 2022 report, where the authors defined it as:

Justice is concerned with setting out the moral or legal principles of fairness and equity in the way people are treated, often based on the ethics and values of society. Social justice comprises just or fair relations within society that seek to address the distribution of wealth, access to resources, opportunity and support according to principles of justice and fairness. Climate justice comprises justice that links development and human rights to achieve a rights-based approach to addressing climate change.

The same IPCC (Feb, 2022) report elaborates the relationship between justice and recognition in the context of climate change:

The term climate justice, while used in different ways in different contexts by different communities, generally includes three principles: distributive justice which refers to the allocation of burdens and benefits among individuals, nations and generations; procedural justice which refers to who decides and participates in decision-making; and recognition which entails basic respect and robust engagement with and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives.

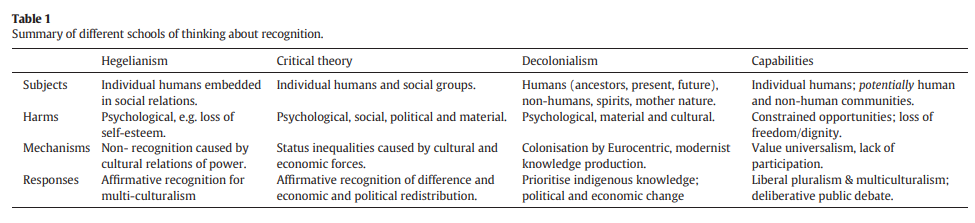

That is, recognition is a foundational principle of justice – whether social, climate, or design justice. Martin, Coolsaet, Corbera, Dawson, Fraser, Lehmann, & Rodriguez, (2016) dive deeper into the meaning of recognition as it pertains to justice, summarizing it from four different schools of thinking, as seen in my screencap of their table (p. 257) below:

Recognition goes hand in hand with cognitive justice, a concept introduced by the Indian development scholar Shiv Visvanathan back in the late 1990s.

Cognitive Justice “demands recognition of knowledges, not only as methods but as ways of life. This presupposes that knowledge is embedded in an ecology of knowledges, where each knowledge has its place, its claim to a cosmology, its sense as a form of life. In this sense knowledge is not something to be abstracted from a culture as a life form; it is connected to a livelihood, a life cycle, a lifestyle; it determines life chances.” (Visvanathan, 1997)

Implementing cognitive justice (CJ) in practice necessitates “an active dialogue between different forms of knowledges and practices, both scientific and nonscientific” (Santos, 2014). Coolsaet asserts putting cognitive justice into practice “involves rethinking the way in which knowledge emerges in modern science, where one side produces and the other passively consumes” (2016). This raises the question whether design research can be just without cognitive justice?

There are numerous definitions of design research in academic literature, but they all have one equation and two variables in common. There is the researcher/research team and there are the researched. The locus of expertise in research has never yet been in doubt. It falls on the side of the action takers who initiate generation and creation of novel knowledge through a structured plan and considered approach (aka research). The recognized expertise of the researched can be laid out according to the intensity of this belief along a continuum of design research methodologies, tools, methods, and approaches – from passive subjects of human centered design research to active co-creators of participatory design research.

However, the insights to inform design remain the purview of the research experts. The participants and co-designers are ‘experts of their own experience’ along for the ride of knowledge creation that will serve to benefit them – directly and indirectly according to the selected methodology, mindset, and approach of the design research team. They are, however, not recognized as peers by the initiators of the research activity. They will not be writing up the notes and observations for peer-review nor reviewing the writing of their peers. Whatever the degree of collaboration and closeness, the separation remains untouched and unquestioned.

Can design research facilitate cognitive justice? Does recognition of an ecology of knowledges diminish or undermine the research process – for instance, what if the peer review of your user research insights comprised the feedback given by the researched in addition to other authorized authors of published literature? The very fact that we do not recognize the feedback on the analysis and insights derived from the data generated by, with, from, the researched as contributing to the ‘rigor’ of the research nor their right to review the actions we may take with the data collected as credible enough for publication is a reflection of the way the world’s knowledge systems are hierarchized. Foregrounding the voices of the researched is not enough for justice. Questioning our own scaffolding for expertise and recognition may certainly be a step forward.

The main argument […] is that there is no global social justice without global cognitive justice. (de Sousa Santos, B., Nunes, J. A., & Meneses, M. P. (2007). Opening up the canon of knowledge and recognition of difference. In de Sousa Santos, B.(Ed) Another Knowledge Is Possible: Beyond Northern Epistemologies)