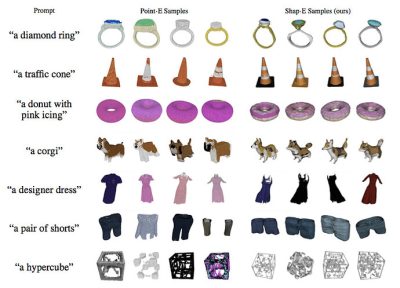

This screencap is from a post made in the Core77 Community boards about the emergence of AI-driven CAD outputs. At first glance, it seems as though its the end of the role of the human being in the industrial design process. And, to me, the situation right now in the first half of 2023 feels similar to early 2005 when it was becoming clear that manufacturing had moved lock, stock, and barrel to China taking all the related industrial design and product development processes with it. These included prototype development and model making as well as CAD work and the generation of alternate concept designs for clients to choose from. Two years ago, I wrote:

A critical inflection point for the expansion and transformation of design practice can be said to have begun around the turn of the century (Bhan, 2004) when designers began to reposition themselves as partners, rather than vendors, to industry (Portigal and Bhan, 2005 November) in response to the changing landscape of manufacturing, outsourcing, and industrial design practice (Bhan, 2005 March).

As I go back and reread my old words from almost twenty years ago, I wonder now where designers can go from here?

On one hand, as always, there are new specialties emerging – Design for AI, for example is 2023’s version of the rise of IA and UX as important disciplines in the practice of digital design from the turn of the century. On the other, as the trend to digitalize everything and think of everything in terms of the virtual swamps all other thinking from consideration, the question of the future remains open in the fields of industrial design and the making of products for humans to use in their everyday lives. For a change, I do not look to academic literature as I have been doing over the past couple of years for insights to contribute to my blog writing. For the most part, scholars are distanced from the issues that designers face right now as some or many more begin to lose their jobs or as entire roles or departments disappear from existence. This is not an exaggeration to anyone who has lived through the last 40 years of personal computing but a pattern that has increased faster and faster ever since. In 1995, I worked with commercial artists in both a design studio as well as an advertising agency, who would create rapid mockups of the visuals and the concepts for client presentations. Does this role even exist now?

Similarly, as the generative design capabilities of AI improve rapidly, I feel its time to ask what the role of the human being will be in the design process, rather than asking what the role of the designer would be as I did back in 2005. I found this article from Italy which discusses this very question, going as far as to quote Phillipe Starck on his putative replacement by a machine. It offers food for thought, in an insightful way – I hesitate to use the word intelligent here.

When Philippe Starck introduced his AI chair for Kartell at the Milan Design Week someone asked him if Artificial Intelligence will replace designers. «Yes», he answered. Yet what makes AI design interesting is not the possibility to make it a substitute for human creativity but a clever addition, for more sustainable manufacturing.

From an industrial and production engineer’s perspective, the position offered by the article is immensely attractive. AI’s contribution is parametric technology to the product design process from idea to manufactured artefact. That is, just like parametric technology was first introduced in the very early 1990s as an “expert system” for AutoCAD and related softwares, able to automagically resize the entire assembly when one component’s measurements were changed, today AI in product design can do the hard work of optimizing materials use and energy use in the manufacturing process. It functions somewhere between Value Analysis of primary and secondary functions and the Carpenter’s problem from OR to optimize and re-optimize parameters within the shaded area of the solution space, as crudely seen in the diagram titled Figure 9. The extended explanation of this is outside of the scope of this blogpost.

From an industrial and production engineer’s perspective, the position offered by the article is immensely attractive. AI’s contribution is parametric technology to the product design process from idea to manufactured artefact. That is, just like parametric technology was first introduced in the very early 1990s as an “expert system” for AutoCAD and related softwares, able to automagically resize the entire assembly when one component’s measurements were changed, today AI in product design can do the hard work of optimizing materials use and energy use in the manufacturing process. It functions somewhere between Value Analysis of primary and secondary functions and the Carpenter’s problem from OR to optimize and re-optimize parameters within the shaded area of the solution space, as crudely seen in the diagram titled Figure 9. The extended explanation of this is outside of the scope of this blogpost.

«People have a phantasmagorical idea of machines», continues Asensio. «In reality, what the generative design programs do is create a space in which man can propose something new and improved compared to the existing one. Within this scenario, the designer represents intention, inventiveness. The software is a very powerful tool to allow it to get where it never could. For example, to make an object more environmentally friendly: more compact for transport, lighter, using fewer materials with equal strength and durability. With generative algorithms, for example, we are able to reproduce exactly the way in which a natural material grows and to imitate its becoming, according to an approach that often calls biomimicry».

Where one would think the Italians with their centuries old legacy of “design” and artisanship would be the first to feel threatened by the AI tools, they are the first to point out (the article is from 2019) that it would be foolish to waste AI on the creative side of making things when it was far more powerful on the production and sustainability side of things.

«Designers, good ones, think and invent outside boxes», says Asensio. «Instead of clinging to positions of challenge to computers, they should therefore understand what the algorithm can do to help them be even more inventive. It is a matter of training and it is no coincidence that we are already working with many schools throughout Europe. All this will allow us to see the world with different eyes. Machines will be for design what photography has been for art: a glorious new beginning, a change of perspective that has led great authors to explore beyond the visible, with expressionism, cubism, conceptual … .. ”

It seems to me, then, that where this AI trend would eat into the creative work would be in disciplines where tangible materials, the investment in energy and manpower, and the time to market were not critical – for example, website design or as the Canva CMO would have it, the graphic design for a slide layout or a brochure. That is, its impact will be similar to that of Aldus Pagemaker (now known as the Adobe suite of products) which triggered the desktop publishing revolution 25 or 30 years ago, I forget. I do remember however that back then everyone was worried what would happen to graphic designers when anyone could layout their own resume with a click of a button. Nothing much happened beyond the increase in numbers of people who imagined fondly they had an aesthetic sense and the eye for harmony, balance, and composition when presenting their digitally crafted portfolios to design schools. Until AI replaces the admissions officer and the faculty who make decisions on the shortlisted portfolios, much less takes over the various tests for the eye that top flight design programs conduct as part of the selection process, it is unlikely that the quality of design talent will degrade.

On the other hand, I can’t help but think that the very people who are foremost in developing and promoting these generative creativity tools will be the first to find themselves being replaced. Big data has already taken over the decision making for “design” in the apps and websites of the tech giants. They don’t need to think about considerations of materials use or circular manufacturing. Nor does it matter whether its important to know whether the chair will fit a human body comfortably. In a way, the very blurring of boundaries that shifts the meaning of the words product designer from tangible products to digital ones will be the ones that will, to put it bluntly, save industrial design’s ass.

The datasets say so.

When asked to write about design strategy, the AI can only write about a logo or a website. There is little else out there on the interwebz, which provide the raw materials that power these engines. Sure “AI is going to make everyone a designer“, desktop publishing was going do the same. In a way, this is the quality convergence that will take place after the divergence that took place after the PR launch of design thinking and everyone is a designer back in 2005. The irony will be in the very words design thinking, given that one thing we’re clear about is AI’s lack of capacity to actually think. It simply simulates the next best predictable outcome within the confines of an opportunity space that has been pre-defined. It can think within the shaded area, not choose the variables and equations that create the shaded area.

I may be becoming a bit obscure, as the rishi once said when he pondered the concept of shunya. But one thing that data scraping of our words and thoughts to feed some engine of creative generation somewhere has taught me is that circumlocution requiring inference may be a better way to preserve one’s original thoughts from appropriation than clear thinking and direct articulation. Maybe the next blogpost will ask the question whether inference is automated as of yet?

This conversation will continue.